Germany’s universe of wine is difficult to understand even in the best of times. And these are particularly complicated times for German wines.

We have come to think of German Riesling, particularly from the Mosel Valley, as at least a bit sweet. Many, including some of the world’s best wines, are just that.

But if you believe the current structure of German wine rules, it is dry Riesling that the country does best. For about a decade, wines primarily known as Grosses Gewachs („great growths“) – the country’s equivalent of a grand cru – have been mandated to be dry.

This reflected a belief, not entirely accurate, that Germans prefer their Rieslings dry. Sweeter wines were primarily sent across the border.

But the world is not so simple. In this most traditional of wine cultures – Riesling has been grown near the Rhine since at least the 15th century – a growing roster of wines is defying easy classification. Often they exist in a complicated realm between dry and sweet. Certainly they can appeal to lovers of both.

What they are struggling with, like winemakers elsewhere, is that sweetness has become a bad word. It is why they often describe the slightly sweet nature of many Rieslings as fruchtig, or fruity. Even that comes with risk. Somehow, dryness has become a default.

„Unfortunately,“ says Johannes Leitz, who makes Riesling in the Rheingau area, „most people want to see the word ‚dry‘ on a label, even when the wine itself would taste better with 11 or 12 grams (of sugar) and they would like it more.“

Logical purpose

It may be disconcerting to consider a wine that’s neither dry nor sweet. But the purpose of such wines, at least in Germany, is utterly logical.

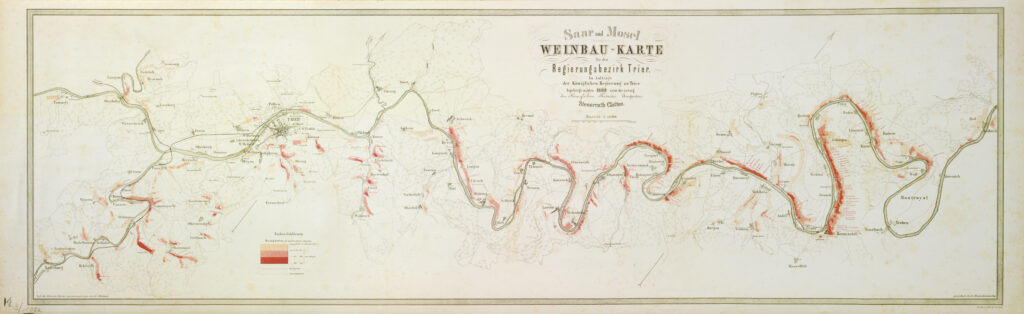

Thanks to a combination of climate and better farming, it’s now far easier to fully ripen grapes in northern Germany, even in regions like the valley of the Saar, a Mosel tributary known for wines that were alternately ethereal or sour.

The prospect of dry Saar wine, once considered tart enough to put Sour Patch Kids to shame, has been finessed by small producers like Erich Weber of Hofgut Falkenstein. Falkenstein’s wines, aged in old wooden casks, can flirt at the edge of dryness. The fully dry, or trocken, bottles are as bracing and deep as great Chablis.

These are complicated wines to understand, given Germany’s current wine laws, which presume a wine to be sweet unless marked otherwise – and set specific, and painfully complex, limits for what constituted dryness.

If a wine wasn’t fully trocken, it could be halbtrocken, or „half-dry.“ It could also be feinherb, which, just to confuse things, has no official definition but tends to indicate wines slightly further along the path to sweetness.

No surprise that many see the limitations of current law – as well as the strict rules imposed by the VDP, the country’s powerful winegrowers‘ association. This has led to a raft of producers making at least some wines that don’t fit comfortably inside the rules.

Among them are so-called estate wines. These bottles, meant as a winery’s everyday effort, are typically sourced from younger vines and less profound sites.

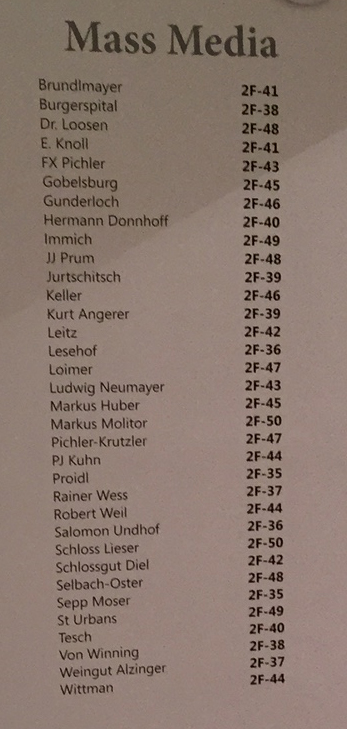

Because their labels rarely say anything about geography, ripeness or sweetness, they have become a chance for today’s winemakers to dabble in a bit of impressionism – often leaving just enough sugar to add charm without being distinctly sweet. This includes bottles from some of the country’s greatest producers, including J.J. Prum in the Mosel and Donnhoff in the Nahe. They are now considered an insider’s secret, one of the best unheralded values in wine.

Snapshot of a place

At the same time, there are more so-called village wines that show a snapshot of a particular town, if not a single vineyard, like the Dhroner Riesling from A.J. Adam. The tiny production focuses on the village of Dhron, which is a few miles from the famous town of Piesport but whose wines have been mostly forgotten.

Owner Andreas Adam focuses on sweet wines, about 60 percent of his production, but also makes a dry wine from his top site, the Hofberg. As for the Dhroner, it often hovers between dry and just short of dry, mostly because Adam would rather leave a bit of extra sugar than tinker with the wine’s acidity. The Dhroner serves a purpose to „show more than only the grape variety,“ he says – specifically, the „texture of the main soil from one village.“

Then there are wines like those from the recently revived Immich-Batterieberg estate in the middle Mosel town of Enkirch, including its CAI, a blend from several vineyards that flirts with dryness but doesn’t fully commit. Or those from Weingut Peter Lauer, in the Saar town of Ayl.

Lauer has gained an American fan base for its asterisks – like the Barrel X, its version of an estate wine, which often lands around 18 grams per liter of sugar (a typical dry wine would have half that). There’s also its Fass 6 Senior Riesling, made from the famous Ayler Kupp vineyard, which hovers in that no-man’s-land just beyond dry.

„You don’t force the wines to be bone-dry,“ says Florian Lauer, who makes the wines for his family’s property. „We accept a certain level of residual sugar, like my grandfather did in 1919.“

The long view helps to explain why sweetness has become so confusing. While we now often consider Germany’s wines to be sweet or fruity, those were an anomaly until modern winemaking arrived after World War II. When vintners relied on indigenous yeast in the cellar and vineyard, their great hope was to complete fermentation and have a dry wine.

Changing tastes

The introduction of commercial yeasts, and the ability to halt fermentation, prompted a midcentury thirst for sweet wines. In 1968, the book „Wines of the World“ noted the winemaking of the time yielded „a sweeter type of German wine than was known 40 or 50 years ago.“ Indeed, a precursor to modern wine law passed in 1958 limited the amount of sugar that could be left to 25 percent.

Back to our complicated relationship with „dry.“ In wine, the balance for sugar is acid, something German Riesling has in spades. It’s only reasonable, then, for wines like the Barrel X or the estate wine from Von Winning in the Pfalz to use sugar, quietly, to finesse a balance of tart and sweet. They can’t call themselves dry, but they have no reason to be considered sweet.

This extends to some top wines. Leitz’s bottling from his Kaisersteinfels vineyard, and back in the Mosel town of Zeltingen, bottlings by Selbach-Oster’s Johannes Selbach of single-vineyard parcels like Anrecht and Rotlay, simply don’t discuss relative sweetness on the label, even if they retain a small amount. The belief is that terroir trumps sugar.

In a way, these are more honest responses than the phantom sweetness that has crept into many American wines. Because so many wine lovers insist on loving „dry“ wines, despite revealing their sweet teeth, we have seen the rise of wines like Gallo’s runaway hit Apothic Red; with its 19 grams per liter of sugar, it would qualify as fully sweet if it were white wine. Indeed, if the German sugar judges descended on Zinfandel, many bottles would technically be halbtrocken.

Back in Germany, there are baby steps to untangle this thicket. After significant blowback from its insistence that Grosses Gewachs all be dry, the VDP unveiled alternative rules to allow sweet versions designated from those same top sites. Sound confusing? That might explain why those revisions have yet to be fully enacted.

But the real story behind this middle ground between dry and sweet is that it marks a return to the traditions of the past – namely, to the old-fashioned cellar work, with native yeasts and old wooden casks, that was once shunted aside.

It is why after a 30-year career, Florian Lauer’s father, Peter, gave up commercial yeasts in 2000 at his son’s urging, and allowed the wines to find their own balance between dry and sweet – a decision for the future guided by a lifetime of following the rules.

„In a winemaker’s life, there’s a certain point where you’ve seen everything, you’ve tasted everything,“ Florian says. „It was something decided by both my father and me together. I think my father was thankful I had this idea.“

From the notebook

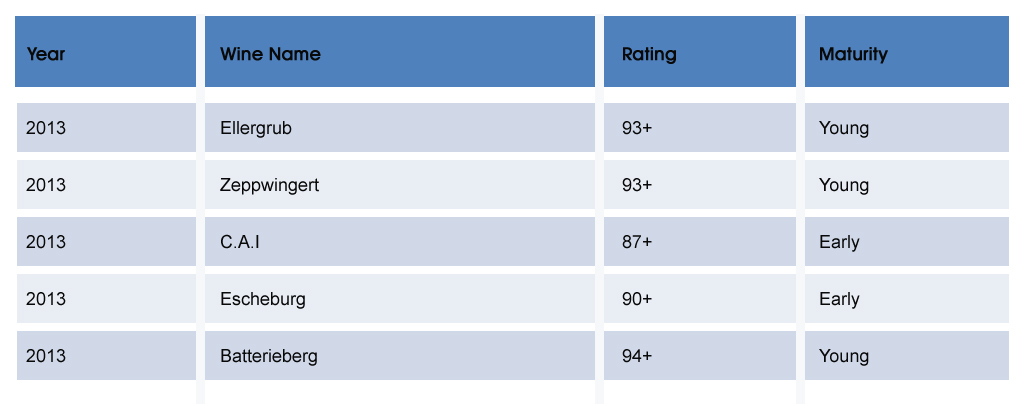

Here are seven German Rieslings that flirt with sweetness but come across as perfectly dry.

2012 Von Winning Estate Pfalz Riesling ($22, 11.5% alcohol): This ascendant estate makes some of the best dry Grosses Gewachs in the Pfalz under the hand of Stefan Attman, but the estate wine is their secret treasure. Showing a ripe texture that’s the mark of the winery, it has perfect integration: cassia, talc, dried lime, verbena, pippin apple. The 14 grams of sugar come through more as weight than sweetness. (Importer: Terry Theise/Michael Skurnik Wines)

2012 Hofgut Falkenstein Niedermenniger Herrenberg Feinherb Mosel ($20, 10.5%): If dry Saar Riesling sounds too trippy, this is a perfect example of feinherb’s charms – frothy and salty and showing a subtle nectary sweetness. Fuji apple, rose hip, talc and a lime-leaf exoticism, plus that remarkable Saar mineral bite. (Importer: Lars Carlberg Selections/USA Wine West)

2011 Peter Lauer Barrel X Saar Riesling ($19, 11%): Lauer wines are still rare on the West Coast, but keep an eye out for the forthcoming 2012. The Barrel X is as friendly a wine as you’ll find from the Saar; this vintage exudes jackfruit and strawberry flavors, and a sappiness to the texture that reflects deft work with that hint of remaining sugar. (Importer: Vom Boden/T. Elenteny Imports)

2012 A.J. Adam Dhroner Mosel Riesling ($28, 12% alcohol): Andreas Adam leaves about 12 g/l sugar in this village wine, which shows itself more as a fullness of texture (also aided by aging in cask). The style veers between austere and juicy, with a rush of yellow plum and tangerine fruit. (Importer: Terry Theise/Michael Skurnik Wines)

2012 Von Schubert Maximin Grunhauser Mosel Riesling Feinherb ($24, 11%): Carl von Schubert’s Grunhauser property, by the Ruwer tributary of the Mosel, has made iconic sweet wines for centuries. But the forthcoming release of its feinherb estate wine is both approachable and intense – chive, sweet lime, austere honeydew skin and citrus pith, and a hint of nectary sweetness for perfect balance. A beautiful example of feinherb. (Importer: Loosen Bros.)

2012 Okonomierat Rebholz Dry Pfalz Riesling ($19, 12.5%): The Pfalz is a stronghold for dry Riesling, and Hans-Jörg Rebholz one of its major proponents. But there’s surprising weight and richness here, thanks in part to the great 2012 vintage – sweet melon to balance the nutmeg spice, celery and peach. (Importer: Rudi Wiest/Cellars Intl.)

2011 Immich-Batterieberg C.A.I. Mosel Riesling Kabinett ($22, 11.5%): The label would hint at its being sweet, but this is Germany’s new dryish side in a nutshell, from Gernot Kollmann’s revival of a historic Mosel site. The dense flavors burst, with tons of nectarine and key lime, lavender, and a sense of sharp-eyed Mosel minerality that’s vibrant without being stark. Keep an eye for the 2012, appearing soon. (Importer: Louis/Dressner Selections)